Sustainable harvesting

The most common of Rokua’s lichens is the light-grey and relatively large star-tipped cup lichen. It is also the best of them for both decorative and practical purposes.

Lichen is a delicate plant that usually grows to its full size in five to ten years, at a rate of approximately five millimetres per year. As the lichen grows, its base decays, so the lichen carpet never grows more than about ten centimetres high. This depth of approximately an extended finger is the thickness that the top of the lichen grows to as the base decays. Therefore, harvesting in moderation does not destroy the lichen, but allows it to grow back every few years.

Harvesting of lichen began in Rokua in the 1920s. The work is very dependent on the weather. Lichen was mainly harvested in wet weather during the summer to prevent it from crumbling during handling. If the lichen was harvested in dry weather, it was first moistened with water from a pond or lake to prevent it from crumbling.

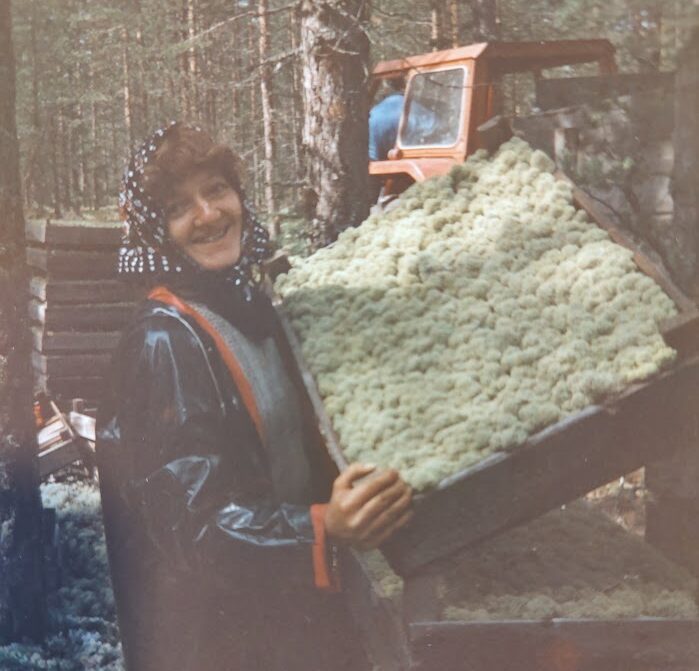

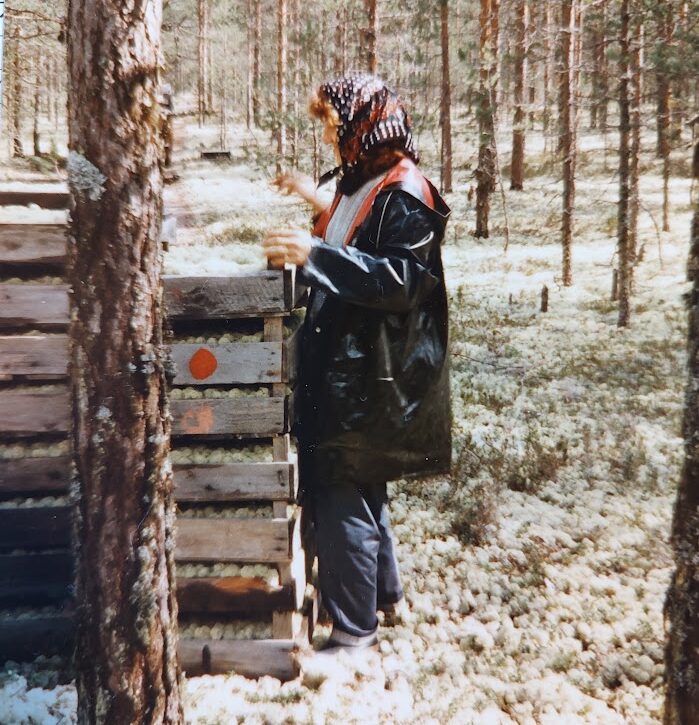

After harvesting, the lichen was carried in sacks to sieving stations where it was poured into a wooden sieve. A low, lattice-like wooden box made of narrow slats was hung from a pole between two trees a few metres above the ground. When the screen is shaken, sand, needles and other unwanted material fall through the bottom, but the lichen remains on the screen. The cleaned lichen was then packed into boxes and salted to prevent the tightly packed and moist lichen from rotting. Salting was later abandoned along with the summer harvest.

Harvesting methods have evolved. In the 1940s the lichen began to be collected in lighter, single-layer wooden boxes for drying, whereas previously it had been sent abroad in moist wooden boxes. Methods of drying the lichen were also developed, using practices known from grain drying.